A personality test for our climate system: the basis for forecasting 'in-between'

Each of us has that one aspect of our personality that people who know us consider typical or predictable. It could be that you snooze your alarm at least twice every morning, or bite your fingernails when you’re nervous, or snort when you laugh too hard. The people you know can count on it happening most of the time. Well, the climate system has its own personality, and as scientists that study it, we are ultimately trying to find its predictable traits and routines.

What is the “in-between” and why it is so difficult to forecast?

First, weather and climate are not the same thing. Weather describes short-term conditions. For instance, it helps you decide what outfit you wore today. Climate describes very long-term conditions, usually by taking the long-term average of temperature, precipitation, etc. Climate helped you decide the variety of clothes and accessories you keep in your closet. If you open your weather app right now, you will notice your daily forecasts stop after 7-10 days. That’s because the atmosphere’s personality is very chaotic. Daily forecasts past 10 days just aren’t very good, which is a complex topic that we’ll talk about in a future post. However, just the fact that scientists can reasonably forecast out that far into the future is amazing. It’s as if weather scientists have built a crystal ball, and the visions keeps getting clearer and seeing out farther than anyone even just a few decades ago could have imagined.

You may also have seen pictures of forecasts that go out decades, even centuries, into the future, usually about how scientists have made reasonings and projections about climate change. Climate scientists understand the system’s “boundaries”, a term that describes the needs and constraints of the physics. Even the most chaotic people have their boundaries, just like the climate system. The atmosphere and ocean work together to settle (think about how we know that a pendulum swings until gravity and air resistance stabilize it).

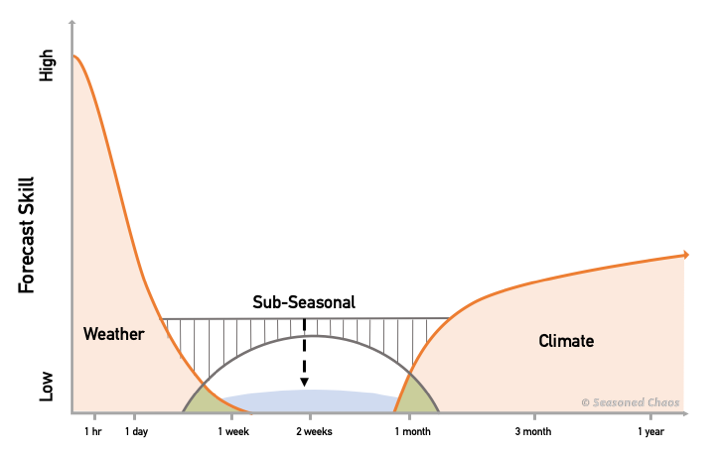

If forecasting weather requires a near-perfect depiction of the chaos, and forecasting climate needs the near-perfect understanding of the balances, forecasting anything in-between those timescales needs both. That’s very difficult. The timescale issue can be summarized in the below figure. This problem often makes scientists go ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. But not every scientist in the field thinks this is impossible.

Forecast skill as it relates to how far out one is trying to forecast; subseasonal prediction is the blue curve beneath the bridge

Why is it worth trying to forecast? Why is there hope?

The Kirtman Group at the Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences accepts this challenge, which brings us to what subseasonal-to-seasonal (subseasonal = within a single season) forecasting means for the non-scientist. As Dr. Ben Kirtman puts it, “Historically, this timescale has been extremely difficult to predict – even called the ‘Valley of Death’ in terms of predictability (note the blue curve in above figure).” Kirtman believes this topic is worth fighting for since these forecasts can be very valuable. Resources can be allotted, and better preparations can be in place, if we know the chances that high-impact events, such as a wildfires or tropical storms, will occur. “As our data, understanding, and prediction tools have improved in recent years, there is now compelling evidence that we can make useful forecasts of chances of extreme weather 3-4 weeks in advance.”

It all boils down to finding that predictable trait mentioned at the beginning. We can guess what the weather and climate will do based on knowing the earth system’s patterns, just like we can guess a person’s behavior by knowing their personality. Like our human brains, the earth system has a way to store “memory”. Therefore, even though there is chaos happening in the system all the time, the system has a background element that lasts much longer than that about 2-week limit of weather forecasting.

Let’s say we are trying to predict the rainfall in the southeastern U.S. a month from now. We need to understand the big-picture relationship between the rainfall in that region and another climate pattern elsewhere. That other feature lasts much longer in time, which means scientists can try to figure out what the atmosphere and oceans are “remembering” back to while they are progressing to its next situation, as seen in the animation below. For example, tropical sea surface temperatures persist for a long time because water warms and cools more slowly than air. We may notice, through statistics and data analysis, that warm sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific (called “El Niño”) are related to a wet southeastern U.S. in the winter. When El Niño is present, we don’t know for sure that it will be rainy in the southeast during winter, but the chances of it happening are much higher. And that is going to be some appreciated information for decisionmakers in a region with a lot of agriculture and fragile ecosystems, such as the Everglades.

Diagram of how a warm ‘blob’ in the tropics could lead to air flow changes and be associated with precipitation elsewhere (usually higher in latitude)

Dr. Kirtman’s lab, as well as other scientists in this field, work on unique, challenging, and valuable forecasting problems, from decadal prediction, to subseasonal prediction of tropical cyclone activity, to the predictability of heat waves, and much more. Over this series of posts, the Seasoned Chaos team is going to discuss the pretty cool topics of this “in-between” forecasting. Keep up with when we post by following us on Twitter @seasonedchaos. We’ll try to be predictable about when we post – once every two months or so – but no promises in this chaotic world. ![]()