Round 1: ENSO is King

In the Pacific, lurking under the ocean surface and riding thunderstorms into the sky is a beast, slow-moving and inevitable yet still chaotic and unpredictable. Today we are here to warn you about ENSO.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO is a climate pattern with a somewhat regular cycle with an oceanic and atmospheric component. The El Niño refers to the oceanic part; the ocean temperatures in the East Pacific off the coast of Peru vary by a few degrees from the seasonal average (which is actually quite a lot). The Southern Oscillation is the atmospheric component which measures circulation that spans the entire Pacific. The EN and SO build off of each other and create rippling climate patterns that are felt across the entire globe.

Norms to Extremes - Suits of ENSO

ENSO has three different phases of its cycle. The two extreme phases are El Niño (warm) and La Niña (cool) and the third phase is the neutral phase. El Niño was termed by fishermen off the coast of South America who noticed unusually warm waters around December. Cold nutrient rich waters are prevented from reaching the surface which hurts the Peruvian and coastal South American fishing industries. The word means little boy or Christ child in Spanish and was used due to the proximity of the warm waters to Christmas.

When ENSO is in the neutral phase, the western tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are warmer than the eastern tropical Pacific, and the surface winds blow from east to west. These winds converge with other tropical winds, causing air to rise and tall storms to form (see how this works). This simultaneously affects the ocean temperatures below the surface. The thermocline describes a layer that separates warm, shallow water and deep, cold water. Normally, in the east Pacific, the thermocline is shallower, which means colder water is closer to the surface. As the winds blow from east to west, the water in the east Pacific is pushed westward along the equator, causing the cold water below to rise to the surface.

During El Niño, the SSTs become warmer in the central and eastern tropical Pacific (off the coast of Peru) and the surface winds weaken or even switch direction! In the ocean, we see warmer water below the surface (deeper thermocline) in the central and east Pacific causing more eastern Pacific storms to form over the warm water.

La Niña is the opposite of El Niño. Ocean SSTs are cooler than average and the east-to-west surface winds along the equator strengthen.

This cause-and-effect loop can be better illustrated below. When you click on an element of the loop - Thermocline, SSTs, and Winds - you can see what generally happens over the tropical Pacific during each of the phases.

This cause-and-effect loop between the thermocline, SSTs, and winds describes what is going on during ENSO events. By clicking on an element of the loop, you should get a new image that shows thermocline, SST, or wind conditions during each of the phases.

Place your bets

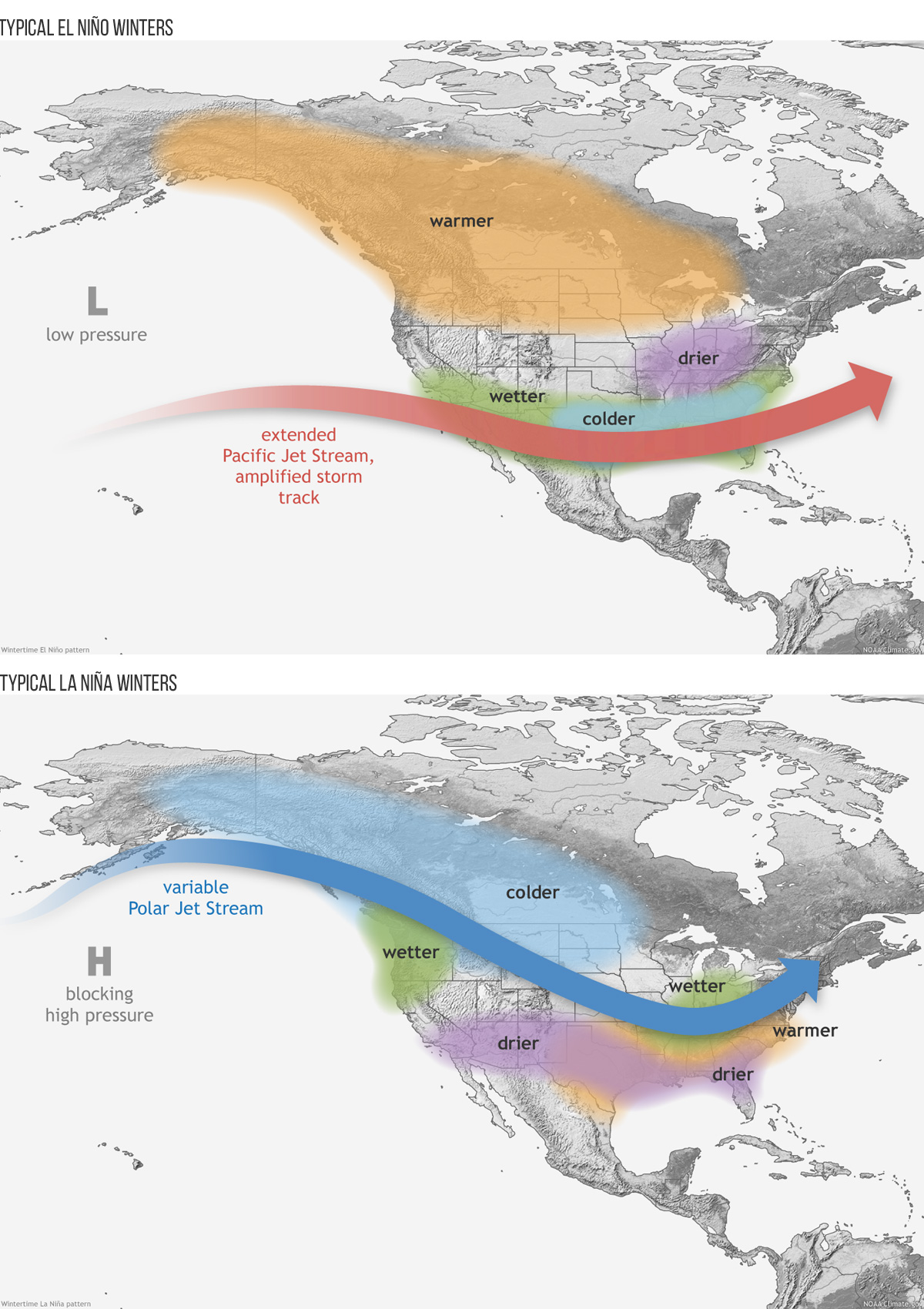

The storms that form over the warm water during ENSO are intense enough that they can affect the global atmospheric circulation by altering the jet stream. The placement and waviness of the jet stream influences temperature and rainfall/snowfall patterns over parts of the U.S. The below figure shows what to generally expect during the ENSO phases. This is why betting on which phase will win is important for forecasting weather.

These weather patterns are typical during El Niño (top) and La Niña (bottom) events. You can see that these patterns are influenced by what is going on with the jet stream. Taken from NOAA Climate.gov blog post.

Be sure to study the stats before placing your bet to get the odds stacked in your favor!

This is part 1 of a two-part blog series about ENSO and predictability. Stay tuned for our next post, which should be out shortly!