The Yellow Brick Road to Predicting Severe Storms

The Hollywood version of severe storms involves dramatic twisters being chased by a group of daring storm chasers slash tornado researchers, various colliding mega-tornado vortices destroying Los Angeles, and a tornado being used as a vehicle of transportation to Oz (a classic).

But a severe storm is more than just tornadoes. The Storm Prediction Center (SPC), the national agency tasked with forecasting the risk of storms, defines severe storms as having one of the following:

- Tornado

- Damaging winds >58 mph

- Hail >1” in diameter (about the size of a quarter)

And this doesn’t even include the other risks like lightning or flash floods (these kill more people every year than hurricanes, tornadoes or lightning!). Despite only 10% of thunderstorms reaching this severe category, the variety of dangers associated with severe storms has led to a big effort in trying to predict them further in advance.

Lift, and Moisture, and Shear—oh my!

There are a few key ingredients that cause a storm to become severe:

Lift refers to a mechanism that supports rising air, AKA an updraft. On a large scale, this mechanism can come from the position of pressure systems and the jet stream. However, this is not enough. Storms also need stronger, small-scale sources of lift, which can come from daytime heating of the ground (triggering convection) or from the collision of very different air masses (a cold vs. warm or wet vs. dry showdown).

In the right conditions, rising air will continue to rise (for the true wx nerds, this is the instability condition). Since the air cools with elevation, eventually air will be cool enough for water vapor to condense, creating “bubbling” clouds.

Moisture is the fuel for the storms to form and grow. Storm clouds grow vertically and need water vapor to keep the condensation of cool air going and going. Most of the moisture for these storms over the U.S. originate from the Gulf of Mexico or Caribbean Sea. Sometimes, there are conveyor belts of fast winds ~2000 ft above the ground from these subtropical regions to the continent, called the Great Plains low-level jet (LLJ). This jet carries moisture as its passenger, consistently “feeding” these storms.

This video depicts a typical large-scale setup for a severe storm event, including the favorable location of the jet stream and Great Plains low-level jet (LLJ) to carry moisture and heat into the U.S. Note that the jet stream is 30,000-40,000 ft above ground while the LLJ is only ~2,000 ft above ground. Next, the relative probabilities for tornadoes, severe hail, and severe wind for March-April-May are shown (should be treated as a climatology, NOT as a deterministic forecast for an upcoming event). These probabilities generally correspond with locations of the LLJ and pressure systems.

Shear is the difference in wind speed and/or direction between upper and lower levels of the atmosphere. We actually already described this in the hurricane post. But, unlike hurricanes, severe storms strengthen with shear.

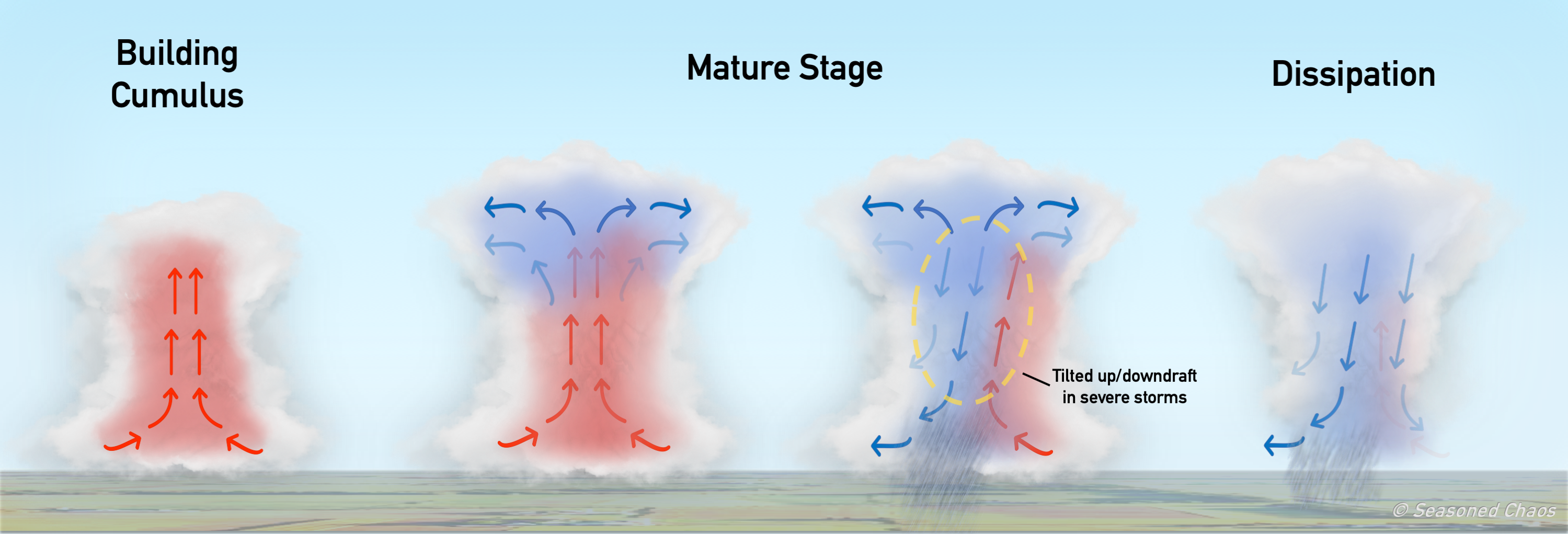

Here’s why: mature thunderstorms have rainfall, which creates a downdraft, a part of the storm where air flows toward the ground. That’s because some rain evaporates on its way to the ground, causing the air to cool. Cool air is more dense, so it sinks even faster to the ground. Storms will dissipate when the downdraft interferes with the updraft.

Shear helps to tilt the storm so that the downdraft and updraft are separated, allowing a storm to keep building. That Great Plains LLJ described before can also provide this shear along with all that moisture (a double threat!).

This depicts the typical life cycle of a severe storm. There are updrafts and downdrafts that coexist in the “Mature” stage, but the storms that reach severe level have a tilted structure (seen in third stage) so that the updrafts can keep doing their thing (fueling storms) for a while without the downdrafts getting in their way.

The Wicked Witches of the East and West (Pacific)

Are you tired of hearing about the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)? Too bad… because ENSO and MJO have such a strong impact on the location of jet streams and pressure systems, they can influence a favorable environment for the large-scale setup of storms, particularly in early- to mid-spring1,2.

For ENSO, the impacts are region-specific and it depends on the strength and persistence of the phase. If a phase (warm El Niño or cool La Niña) is strong such that it persists past the winter peak and continues into spring, it has different impacts than from a phase that is weakening after its winter peak.

One noteworthy tropical condition is a strong and persistent La Niña, which can influence the setup of a strong Great Plains LLJ (encourages shear and transport of moisture) and passage of low pressure systems (encourages large-scale lift) over parts of the Midwest, Ohio Valley, and southeast U.S. In fact, the probability of widespread tornado outbreaks over much of the Ohio Valley/southeast increases to ~50% in the mid-spring during these strong La Niñas!

Then, ![]() somewhere over the Pacific

somewhere over the Pacific ![]() …we have the MJO. Storminess and rising air over the western Pacific – phases 3, 4, 5, 6 – are linked to suppression and sinking air over the northeast Pacific3. This increases the likelihood of high pressure systems to form over much of the eastern U.S., including a LLJ to set up on the western side of the high pressure system (part of clockwise rotation).

…we have the MJO. Storminess and rising air over the western Pacific – phases 3, 4, 5, 6 – are linked to suppression and sinking air over the northeast Pacific3. This increases the likelihood of high pressure systems to form over much of the eastern U.S., including a LLJ to set up on the western side of the high pressure system (part of clockwise rotation).

There’s no Place Like Home

Despite these remote influences, severe storms and tornadoes still require small-scale and local mechanisms of lift, instability, shear, and moisture. That means that outbreaks can still occur even when there are “unfavorable” phases of ENSO and MJO, or vice versa.

It is still really powerful to have the information that severe storms are more or less likely in the next 2+ weeks, and it is exciting that current science points to helpful links between the likelihood of storms and remote climate phenomena. This gives the SPC and regional communities advanced notice to prepare for such deadly and costly disasters.

P.S. If you are curious about the Great Plains LLJ and its influence on other things, like summer rainfall, check out this paper!

Footnotes:

1Lee, S., Atlas, R., Enfield, D., Wang, C., & Liu, H. (2013). Is There an Optimal ENSO Pattern That Enhances Large-Scale Atmospheric Processes Conducive to Tornado Outbreaks in the United States?, Journal of Climate, 26(5), 1626-1642.

2Lee, S. K., Wittenberg, A. T., Enfield, D. B., Weaver, S. J., Wang, C., & Atlas, R. (2016). US regional tornado outbreaks and their links to spring ENSO phases and North Atlantic SST variability. Environmental Research Letters, 11(4), 044008.

3Kim, D., Lee, S., & Lopez, H. (2020). Madden–Julian Oscillation–Induced Suppression of Northeast Pacific Convection Increases U.S. Tornadogenesis, Journal of Climate, 33(11), 4927-4939.