Things are Getting Heated: The Science behind the Polar Vortex and Stratospheric Warmings

The “bubble” we live in and where our weather happens is just one thin layer of the atmosphere called the troposphere. Above that is the layer where dreams are made…well, that is if your dreams involve snowstorms, record cold, and other wild weather…

In this post, we have two scientific experts: Amy Butler, a research scientist from NOAA Earth Systems Research Lab, and Simon Lee, a Ph.D. student from University of Reading. They will chime in on their understanding of this layer called the stratosphere as well as how it influences subseasonal-to-seasonal forecasting.

What is the Polar Vortex?

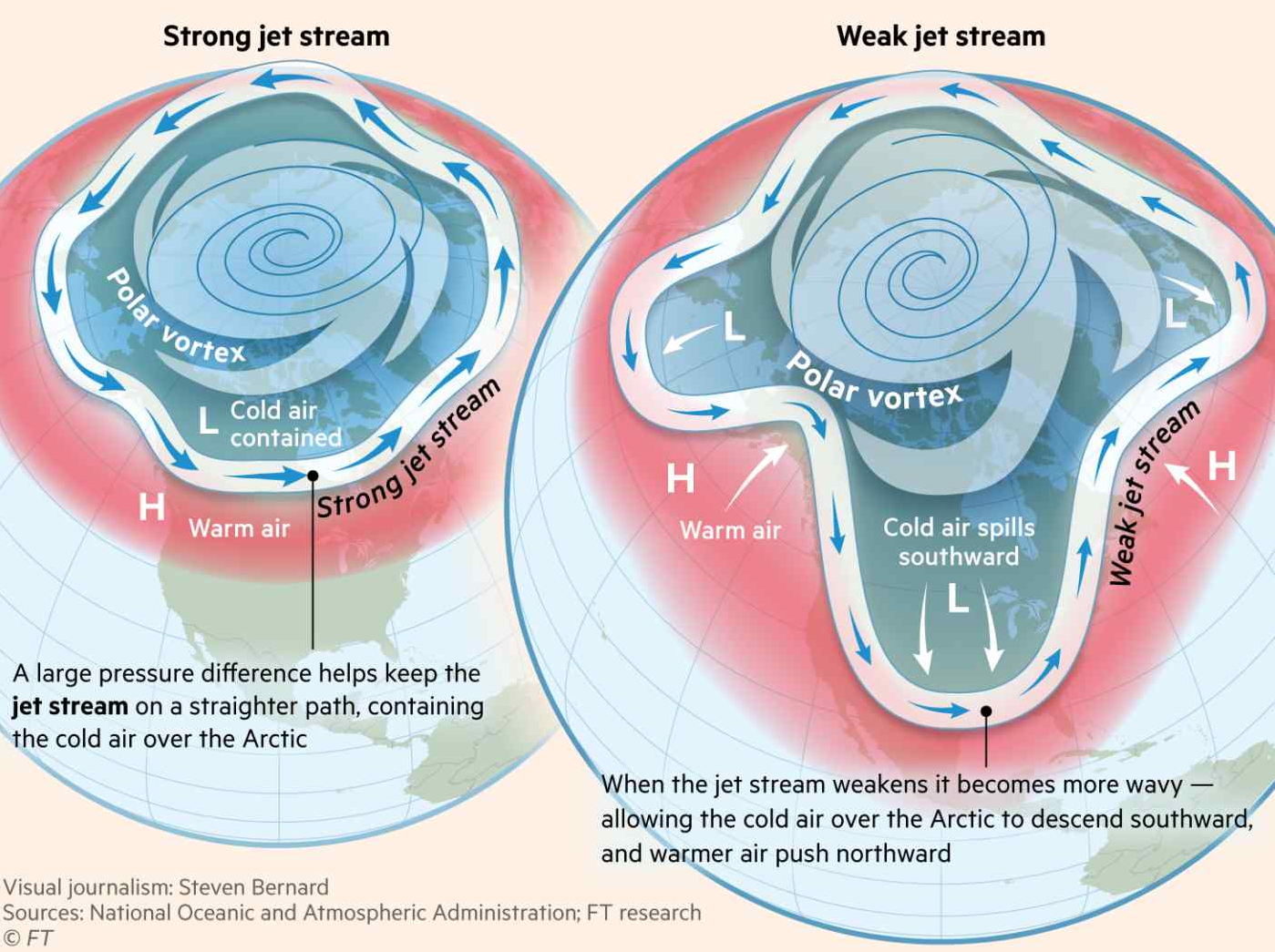

You may have heard about the stratosphere because it is home to the ozone layer, protecting us from the sun’s harmful rays. Every fall, the polar stratosphere loses sunlight and cools. This causes a large difference in temperature in the north-south direction otherwise known as a temperature gradient. This forms the polar vortex, a belt of rapid winds that flow from west to east. The stratospheric polar vortex can be found “high above the surface (10-50 km [6-30 miles]) encircling the Arctic during winter… Within the polar vortex, the air is extremely cold, usually below -50°C [-58°F]. You could think of [the polar vortex] like a spinning top,” Simon Lee explains.

And a spinning top only stays upright when it’s going fast and remains undisturbed. Amy Butler explains why that doesn’t happen sometimes: “The polar vortex… is not always just passively blowing around, but can be both affected by weather patterns and, in turn, drive persistent weather patterns. One event that really demonstrates this two-way coupling is a ‘sudden stratospheric warming’ (SSW) of the polar vortex.”

This graphic explains the influence of the polar vortex on the jet stream, and how that either keeps cold air north (left) or sends cold air to the mid-latitudes (right). Graphic credit given to Financial Times Ltd, published on Feb 20, 2021.

Stratospheric Mood Swing

A sudden stratospheric warming event is, as you can guess, when the (polar) stratosphere suddenly warms. But perhaps we should call it a drastic warming event. Most other climate events we’ve discussed change over months or years. However, an SSW can cause the temperature to rise 50°C (90°F) in just a few days, sometimes climbing above freezing! Although this change happens quickly, the temperatures in the lower stratosphere stay warm for weeks (which makes it subseasonal so we can legally write about it). So what does this stratospheric mood swing mean for our polar vortex?

When the temperature at the pole warms, the temperature gradient decreases which means the winds blowing around the polar vortex get weaker. “Think of this like the spinning top wobbling.” And even though these changes are happening way above our heads they have big impacts on our weather.

This is where the Arctic Oscillation (AO) comes in. The AO is a pattern of high and low pressure that affects the jet stream in the upper troposphere. The negative phase of the AO means the jet stream becomes wavier and moves further south (in the Northern Hemisphere) which allows for cold air from the Arctic to spill into the mid-latitudes (where many of us live). When the polar vortex experiences an SSW we usually enter the negative phase of the AO. This is why the polar vortex becomes relevant when there’s a cold snap in the United States.

Can we Predict a Polar Vortex Disruption or SSW?

In a previous blog about ENSO we talked about the differences between deterministic and probabilistic forecasts when predicting the phase of ENSO. Well, the same idea can be applied for polar vortex disruptions and SSWs. When looking at deterministic forecasts, or exact dates, polar vortex location can only be skillfully predicted about 10-12 days in advance1. On rare occasions SSWs may be predicted 20-25 days before the event, but this does not happen often.

If scientists just want to know whether or not a polar vortex event or SSW will occur for the upcoming winter, “there is evidence of probabilistic skill on much longer timescales (up to seasonal).” These forecasts use the knowledge we have about other weather and climate events going on in the atmosphere (such as blocking) to determine the likelihood of changes occurring in the polar vortex. Even if we do not know if an SSW will occur, predicting a weakened polar vortex can be just as useful for forecasting.

A 16-day forecast of the polar vortex produced by Simon Lee. Plotted is the winds (shading) and geopotential height (black contours, lower GPH value = colder air) at 10 hPa to represent stratospheric flow around the Northern pole. To give you an idea of the height we are talking about: the surface pressure is usually represented around 1000 hPa, the pressure where planes fly is around 250-200 hPa, and pressure continues to decrease as you go towards space. Therefore, 10 hPa is very high up in the atmosphere! As the animation progresses you can see the vortex wobbling like a top as previously mentioned. To see more real-time forecasts relating to the polar vortex and sudden stratospheric warmings, including those that go out to 35-days (WOW), check out Simon’s website. We 10hPa/10hPa recommend.

SSW-indows of Opportunity

If you’re still wondering how this relates to you on the ground and not miles up in the atmosphere, during SSWs, predictions for the temperatures that we experience day to day are more skillful in certain regions (3 to 4 weeks ahead compared to the normal 6 to 10 days). Amy calls these “forecast windows of opportunity” because a weak or strong polar vortex tends to last for many weeks giving a stable component to the weather pattern pie.

This year there was a major SSW on January 5th, 2021 which meant that “the probability of a negative AO was significantly increased for the next ~2 months”. The SSW and negative AO meant that there would likely (not definitely!) be increased cold air outbreaks, shifted jet streams, and changes in precipitation over longer periods of time.

The recent SSW contributed to the conditions that led to the deadly winter storm in Texas. But the opposite can happen too; a polar vortex can intensify, causing a positive AO, bringing record warmth to the mid-to- high latitudes, like in Siberia in 2019/20202.

Although models have struggled to simulate the polar vortex, in the last 10-15 years our ability to predict SSWs has improved. Amy mentions that it will be important in the future to improve how the stratospheric and surface processes affect one another within the models in order to improve the skill of our predictions.

Friends in Low (Altitude) Places

The AO and related SSWs are no strangers to the weather pattern pie. It is tricky to understand just how the AO intertwines with other climate phenomena like ENSO or the MJO. One reason for the difficulty is that we only have 26 well-observed SSWs dating back to the beginning of the satellite era (they only happen 6 out of 10 winters!), which is too few to draw strong conclusions about links to other climate features. Some in the scientific community even find it hard to distinguish between the NAO and the AO, and Amy even says “The NAO is essentially the same thing as the AO” just in different regions. However, scientists, like Amy and Simon, are confident that the AO and the stratosphere can be influenced by ENSO and the MJO. For example, El Niño can increase the likelihood of an SSW in winter by ~30%3 and SSWs are also more likely following certain phases of the MJO4. “Because ENSO and the MJO have their own influence on weather patterns, if an SSW or other polar vortex event occurs, its ability to influence surface weather in the following weeks likely depends on what ENSO and the MJO are doing.” Basically, as Simon puts it: “The stratosphere is important, but it is just one piece of the puzzle.”