Whitewater Rafting Down an Atmospheric River

Bio: Dr. Breanna Zavadoff is a former member of the Kirtman group who attended the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science from 2016 to 2020 when she graduated with a PhD in Meteorology and Physical Oceanography. During her time at UM Breanna performed research on a variety of climate phenomena including atmospheric rivers that affect western Europe.

Before any whitewater rafting trip, one should always be sure they have everything they need. Life jackets? Check! Paddles? Check! What if, however, the river whose rapids you set out to conquer is found in the sky and isn’t really a river at all? Although these special “atmospheric rivers” can’t be explored with boats or paddles, Seasoned Chaos is here as your certified atmospheric river whitewater rafting instructor to safely guide you through the bumps, twists, and turns that come with navigating these unique bodies of water.

Class I/II Rapids: If they aren’t rivers, what are they?

Though not considered a river in the traditional sense, atmospheric rivers are similarly described as long, narrow filaments of water vapor that can extend for hundreds of thousands of miles. In the same way a river carries water downstream, each atmospheric river carries copious amounts of water vapor through the air above our heads. They are responsible for greater than 90% of moisture transport from the tropics towards the poles and develop most frequently during the winter months over midlatitude ocean basins. In fact, a single atmospheric river can transport more water within it than 27 Mississippi rivers combined!

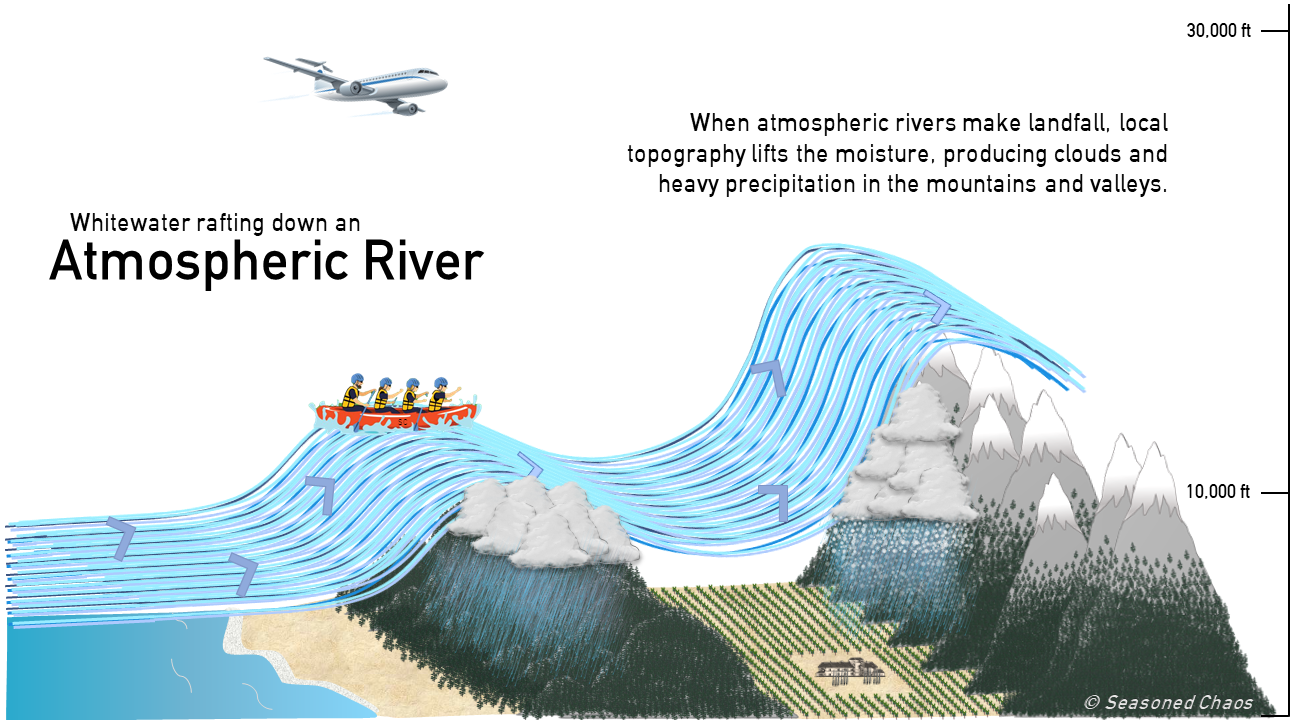

Get your rafts, we’re going for a ride! Atmospheric rivers are powerful transporters of moisture, as depicted above. As they approach landfall, topography lifts the moisture, causing it to cool and condense into clouds and precipitate out. This provides the region with an important water supply. But sometimes there is so much precipitation that it can trigger deadly landslides and flooding.

Like many other components of the Earth system atmospheric rivers can be influenced by different climate variability modes, such as those in our weather pattern pie. For atmospheric rivers impacting the US West Coast, shifts in the jet stream over the North Pacific driven by the phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation dictate whether atmospheric rivers will make landfall at higher latitudes over the Pacific Northwest or lower latitudes over California. Meanwhile, the phase of the Madden-Julian Oscillation has been shown to affect how frequently atmospheric rivers develop over the eastern Pacific. Across the pond the North Atlantic Oscillation forces similar shifts in the jet stream over the North Atlantic, which impacts atmospheric river landfalls over western Europe. Achieving a greater understanding of the nuanced relationships between atmospheric rivers and these different climate variability modes could help forecasters predict where atmospheric rivers will most likely make landfall on both subseasonal and seasonal timescales1.

Class III/IV Rapids: The good, the bad, and the ugly

Given the mind-blowing amount of water vapor atmospheric rivers move around on a daily, monthly, and yearly basis, it should come as no surprise that atmospheric rivers are integral components of the global water cycle. This is especially true for the US West Coast, as atmospheric rivers provide the region with anywhere from 20-50% of its annual precipitation and even serve as persistent drought busters. Furthermore, atmospheric rivers are heavily relied on to replenish California’s reservoirs, thus playing a primary role in the state’s water management system.

While these are all examples of the beneficial, tranquil nature of atmospheric rivers they also have a harmful side, not unlike the turbulent crashing of Class IV whitewater rapids. This is because when atmospheric rivers are particularly long lasting, occur one after the other, or carry extreme amounts of moisture they could be responsible for excessive precipitation events that can lead to devastating local flooding, debris flows, and infrastructure damage.

This “ugly” side of atmospheric rivers was on full display in late February 2019 when an atmospheric river dumped 10 to 15 inches of rain over California’s Russian River Watershed in just 36 hours. Such an intense influx of rain quickly saturated the ground, forcing much of the rain to runoff into the nearby Russian River. Near the town of Guerneville the river swelled to 45.4 feet, more than 13 feet above flood stage, leading to widespread flooding that closed roadways and cut off neighborhoods. Additionally, almost 2000 homes and businesses were affected by the flooding, accruing an estimated $155 million in damage.

A satellite image of Total Precipitable Water (amount of water that can be condensed out of the column of atmosphere) from February 25, 2019 through March 1, 2019, showing the atmospheric river that affected the California’s Russian River Watershed. Check out CIMMS archive to see real-time images and learn more. You can also make your own gif starting/ending at any time within the archive by using this SC Jupyter notebook

Class V/VI Rapids: A sharpening double-edged sword

As with all other high-impact weather phenomena, there is a growing interest in how atmospheric rivers will evolve with climate change. Climate modeling studies performed within the last decade have all pointed towards the same conclusion: in a warming world atmospheric rivers will become more intense due to an increase in available atmospheric moisture. This finding is rooted in what is known as the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship, which states that as air temperatures increase the amount of moisture the atmosphere can hold also increases.

Not only are atmospheric rivers projected to become stronger with climate change, they are also expected to occur more frequently. If emissions continue at the “business as usual” rate2, climate models show that across the globe atmospheric river frequency and strength could increase by as much as 50% and 25%, respectively. So, what does all this mean for the people who rely on atmospheric rivers as a water resource?

As mentioned in the last section, the residents of West Coast states rely on extreme precipitation associated with atmospheric rivers. Climate change is already contributing to existing water resource challenges in the region by eroding mountain snowpack, reducing the frequency of precipitation, and prolonging persistent drought conditions. On the flip side, atmospheric river related extreme precipitation events are projected to become stronger and more frequent due to an increasingly warmer climate.

The consequence of this hydrologic tug-of-war is that, as temperatures continue to rise, atmospheric rivers will contribute more towards total annual precipitation along the US West Coast, which means atmospheric rivers will be more heavily relied on for the generation of water resources than ever before. However, this will be a double-edged sword, as these water-bearing atmospheric rivers are projected to become more extreme, delivering greater amounts of precipitation per event which will generate more frequent and widespread flooding while also putting more strain on infrastructure and water management systems. With the impacts of atmospheric rivers poised to become even more challenging to manage in the future, enhanced subseasonal to seasonal prediction of these phenomena will act as the life jackets, paddles, and rafts helping us navigate the increasingly formidable rapids of future atmospheric rivers.

CIMMS archive (MIMIC-TPW imagery access) and Kayla Besong (Jupyter notebook to create gif)

Footnotes:

1Zavadoff, B. L., & Kirtman, B. P. (2020). Dynamic and thermodynamic modulators of European atmospheric rivers. Journal of Climate, 33(10), 4167-4185.

2Check out Seasoned Chaos writer Kelsey Malloy’s video on what a climate model is and how it’s used to understand past, present, and future climate.