CSI: SC – The Spring Predictability Barrier

Welcome to Climate Science Investigation (CSI): Seasoned Chaos where today we will be investigating the cold case file of the Spring Predictability Barrier. The Spring Predictability Barrier, known amongst climate friends as the SPB, is a widely known forecasting headache. It describes a reduction in ENSO forecast skill for the May-June-July season. While many people love the springtime transition from cold winter darkness to warm spring days, state-of-the-art models in February, March, and April are robbed of predictive skill for May-June-July ENSO conditions. Since winter is usually the peak of ENSO and the events often decay in spring, we lose ENSO’s predictable nature, thus resulting in the menacing SPB.

Meet the Victims

Who are the victims of the menacing SPB? Surely society, forecasters, and eager armchair meteorologists suffer from the lack of ENSO predictability during spring. But if we look closer, it is actually our forecast models that are suffering from the springtime barrier. They are, after all, the ones being robbed of ENSO predictive skill.

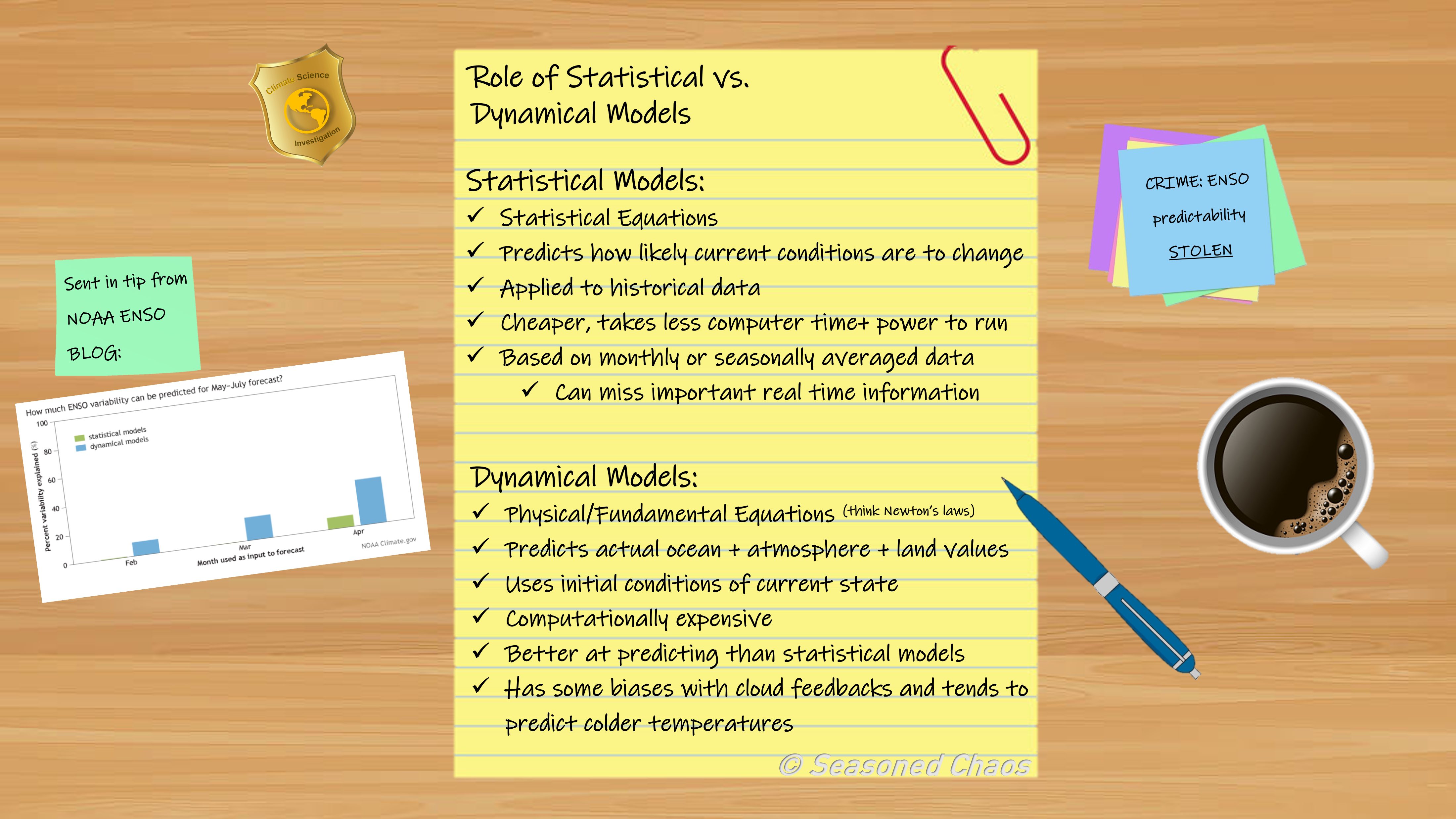

Statistical and dynamical models are a forecaster’s go-to tool. Because they work tirelessly to predict the future, they not only light up our computer screens, they light up our lives! As we try to puzzle together what the future oceanic-atmospheric conditions may be, we depend on our friends, the statistical and dynamical models, to help us make subseasonal and seasonal predictions and, for most of the year, they are pretty good at doing this. It is just during spring that our reliable tools start to display some unusual behavior.

Now that we have some information on our victims, let’s dig into potential suspects in this case. Who or what is exactly behind this menacing SPB?

Suspects At-Large

Suspect #1 Transitional Season

Springtime brings challenges to prediction through chaos-driven errors. Our case is a “crime of opportunity” due to ENSO being in a transitional period after its winter peak. Sea surface temperature and sea level pressure anomalies - departures from “long-term average” - are weakest during this time, while the noise (a measure of chaos) in the tropical Pacific air-sea system remains high. Therefore, the signal to noise ratio is small in spring and forecasts are more sensitive to variability. The smaller anomalies make it harder to “catch” which phase ENSO we will be going into for the coming year.

Suspect #2 The coupled atmosphere-ocean system: the climate Bonnie and Clyde

Another suspect in the case of robbed predictability is the coupled atmosphere-ocean system. Blame can be placed on the Bjerknes feedback, a mechanism by which ENSO events develop and sustain themselves in a coupled atmosphere-ocean system. Lower sea surface temperatures in the spring weaken the coupling between the ocean and the atmosphere, reducing the predictability that both the ocean and the atmosphere provide.

Scientists’ limitations in gathering data escalates the weak coupled atmosphere-ocean system’s crime. In cases when El Nino is developing, the future ocean state is highly dependent on initial ocean conditions. Models are only as good as the data we give them. We have limited observations of ocean temperature, especially below the surface, which causes our models to underrepresent the current state of the ocean. If a model is a little off in their forecast of winds, thunderstorms, or sea surface temperatures (SSTs), these initial errors grow over time because of the climate feedbacks. These errors will continue to snowball until after spring. As ENSO matures, SST anomalies grow and the stronger coupled system provides higher ENSO predictability.

Suspect #3 Asian Summer Monsoon

The final suspect in this case is the Asian summer monsoon, who has always been jealous of ENSO’s success at captivating much of the globe through its influence on climate. “Monsoon” comes from the Arabic word “mausim”, meaning “seasonal reversal of winds”, originally termed by sailors in the Arabian Sea who noticed this wind reversal that coincided with changing rainfall patterns. This wind shift is due to the transitional seasonal heating over South Asia from winter to summer. The Asian summer monsoon impacts billions of people directly and is a key (lime) slice of the weather pattern pie itself, making it a whole other topic that we’ll cover in a future post.

Okay, okay, now that we covered the suspect’s bio, back to the crime at hand. It’s normal for ENSO and the Asian monsoon to fight over who gets to control the easterly trade winds in the west Pacific. They have come to an agreement that the Asian summer monsoon can have control in the spring and summer and ENSO can have control in the fall and winter. But sometimes the Asian summer monsoon is greedy! When the monsoon is strong, it can invoke too much control over the trades and further weaken a coupled atmosphere-ocean system, causing ENSO to be less predictable the following winter/spring. Essentially, the Asian summer monsoon is eager to steal the limelight from ENSO when it can.

The tricky part is that the tropical Pacific winds are hard to predict in the spring regardless of ENSO or the monsoon. Since the winds are hard to predict, this makes ENSO and the monsoon hard to predict. Plus, the winds are a part of our coupled ocean-atmosphere system (hint hint, suspect #2). It’s ultimately a case of the chicken and the egg. Overall, while the monsoon is guilty of some crimes, whether these crimes are tied to the SPB of ENSO or are part of a different case entirely, is inconclusive.

Monsoon animation features the seasonal cycle of rainfall advancement/retreat. Gif courtesy of Google Earth Engine, which uses data from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS) rainfall dataset.

Cold Case

While there are many potential suspects for this case, the reality is that in an individual year, many of the suspects could be working together or that one suspect is not necessarily the culprit this time. So, unfortunately we are left with a cold case. You can see how our suspects continue to get away with robbing ENSO predictability in the spring.

Special thanks to ENSO Blog’s Emily Becker for her help in the development of this post. Her suggestions improved its accuracy and clarity.

References:

- ENSO Blog on the spring predictability barrier.

- Lopez, H., & Kirtman, B. P. (2014). WWBs, ENSO predictability, the spring barrier and extreme events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 119(17). https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd021908

- Duan, W., & Hu, J. (2015). The initial errors that induce a significant “spring predictability barrier” for El Niño events and their implications for target observation: Results from an earth system model. Climate Dynamics, 46(11-12), 3599–3615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-015-2789-5

- Larson, S. M., & Kirtman, B. P. (2016, July 27). Drivers of coupled model ENSO error dynamics and the spring predictability barrier - climate dynamics. SpringerLink. Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00382-016-3290-5

- LAU, K. M., & YANG, S. O. N. G. (1996). The Asian monsoon and predictability of the tropical ocean-atmosphere system. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 122(532), 945–957. https://doi.org/10.1256/smsqj.53207

- Kirtman, B. P., & Shukla, J. (2000). Influence of the Indian summer monsoon on enso. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 126(562), 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49712656211