Demystifying Machine Learning in Climate Science

Robots are taking over the world!!!

Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on your feelings toward robots), artificial intelligence (AI) has provided groundbreaking advancements and improvements to our lives without involving evil-robots-taking-over-the-world. In fact, misconceptions about AI often result in fear, despite AI being used all around us: filtering of your inbox to spam, your Amazon Alexa or Google Home, facial recognition to unlock your phone, fraud detection for your bank account, the list goes on and on.

AI in Climate Science

Not only has AI improved technologies in everyday life, but it is also making great strides in the climate science field. Particularly useful in the scientific community is machine learning, a subset of AI which involves training a model to “learn” via mathematical calculations to reduce its errors. Machine learning could instead be called “algorithm optimization” which would better encapsulate the mathematical and statistical processes involved, but that just isn’t as catchy.

While applications of machine learning in atmospheric science can date back to the 1960s1, recent improvements in data quality and availability, processing power, and computer science techniques have catapulted machine learning to the forefront of data science methods. Recent applications include global weather prediction2, extreme event detection3, data reconstruction4, rapid intensification of hurricanes5, and subseasonal-to-decadal climate predictability6, which you may remember from our weather pattern pie.

Speaking of pies, imagine that your grandma made the best key lime pie and you wanted to recreate it, but she keeps the recipe a secret. You try to figure out which ingredients you need and how much of each to use. So, you take your best guess at the ingredients and ratios needed and bake a key lime pie. But when you taste it, you realize it needs a bit more cream. You start over and add cream, but now realize you need to take out some sugar. You bake pies over and over again, each time getting just a little closer to grandma’s perfect pie until FINALLY you find the perfect recipe for a key lime pie that tastes just like Grandma’s!

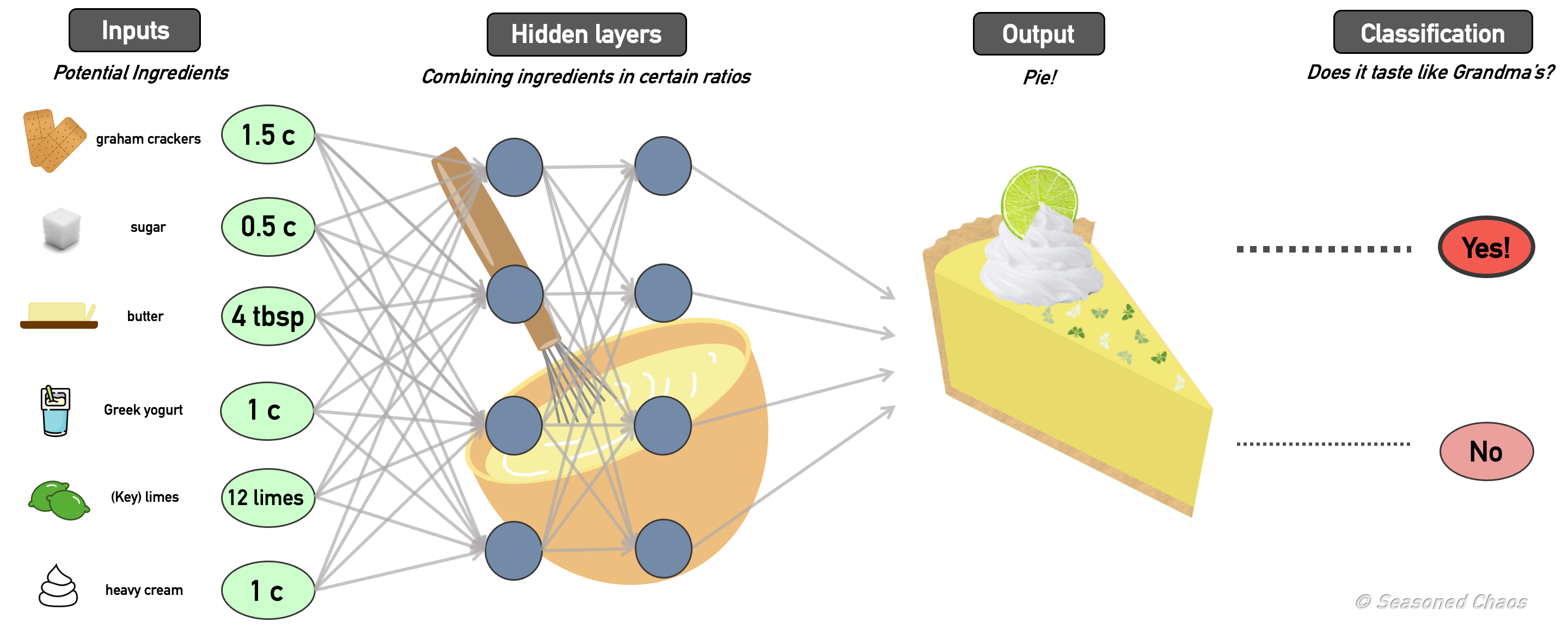

This fine-tuning recipe process is similar to how artificial neural networks, a frequently used type of machine learning, work. Originally inspired by a biological neuron network, an artificial neural network takes in information (ingredients), passes the information through a series of processing steps (combining ingredients in certain ratios), and gives an output (pie). The neural network model is trained by comparing the network’s predicted output to the actual value (ie the truth) and stepping backwards through the model to correct its errors. This is an iterative process that is repeated many times until the network is optimized to make a good prediction.

The process of fine-tuning your Grandma’s recipe can be used as an analogy for a neural network. (And yes, the Seasoned Chaos team may have a pie obsession…)

Opening the Oven (Black Box)

As scientists, we not only want a model to make a good prediction, but we want to know why it made a good prediction. After all, a machine learning model is only as smart as the scientists designing it. Scientists have historically been cautious to use ML as it is commonly thought to be a black box. ML procedures were considered “mysterious” in the sense that they couldn’t be replicated or interpreted with only basic knowledge of mathematics/physics. But this is no longer the case! We use interpretable models and apply explainability methods to allow us to understand precisely how an ML model makes its predictions. These eXplainable Artificial Intelligence, or XAI, methods highlight important patterns for the predictions which allow the user to understand the network’s decision making process7,8. We use explainable and trustworthy machine learning techniques to:

1. Gauge Trust in Model

Did the model actually learn something real or did it just get lucky? We want to ensure

that the model is making a good prediction for the right reasons, or figure out why it was wrong. Using XAI, we can learn what input features the model deemed important and verify the network’s prediction strategy.

2. Learn New Science

Once we have established trust in our model, we can analyze what the model learned. This can help us discover new sources of predictability, disentangle signals from the chaotic noise, and find relationships within the climate system we didn’t know were there.

3. Optimize

Simply put, using ML can help us do science better and faster. We can fine tune our approaches and process large amounts of data efficiently. This can help with data-intensive calculations that are often involved in climate processes, such as tracking hurricanes, identifying atmospheric blocks, and sifting through large amounts of climate model data.

It is important to remember that ML is another tool in a climate scientist’s toolbox. Many standard approaches using statistics, dynamics, and theory for scientific analysis are still effective and valid, and machine learning is an exciting and innovative addition. For example, in a previous post, we discussed research using these approaches to show how the state of the atmospheric and oceanic states of the tropical Pacific can affect weather in the United States on subseasonal (2 week - 2 month) timescales. In my current research, we study a similar problem by using artificial neural networks to make subseasonal predictions of U.S. rainfall using the state of the tropics. By applying the XAI techniques, we can then determine which features in the tropics the model deemed important for its prediction (such as the El Niño/La Niña region, the MJO region, and perhaps regions we hadn’t looked at before). We are also able to quantify how confident the network was in its prediction to identify more predictable time periods, known as forecasts of opportunity. We can assess how these predictable time periods change over long periods of time and how these predictable states may change in the future9. Machine learning allows scientists to investigate complex and interconnected climate phenomena in a digestible way to push scientific knowledge farther than ever before.

Today, we can open the black box and understand what and how ML models have learned. ML is not robots taking over and it is not magic. Instead, it is a powerful technique that can help scientists ultimately learn new science, perhaps while enjoying a perfectly baked slice of key lime pie.

For additional information, check out these great YouTube videos on explainable machine learning in climate science from the Barnes Group at Colorado State University.

And check out this in-depth tutorial for applied machine learning for climate scientists including step-by-step example code.

Footnotes:

1Glahn, H. R. (1964). An Application of Adaptive Logic to Meteorological Prediction, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 3(6), 718-725.

2Weyn, J. A., Durran, D. R., & Caruana, R. (2020). Improving data-driven global weather prediction using deep convolutional neural networks on a cubed sphere. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 12, e2020MS002109.

3Reichstein, M., Camps-Valls, G., Stevens, B. et al. (2019). Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 566, 195–204.

4Kadow, C., Hall, D.M. & Ulbrich, U. (2020). Artificial intelligence reconstructs missing climate information. Nat. Geosci. 13, 408–413.

5Ko, M. C., Kubat, M., Gopalakrishnan, S., & Chen, X. (2021). The Development of a Consensus Machine Learning Model for Hurricane Rapid Intensity (RI) Forecasts with Hurricane Weather Research and Forecast (HWRF) Data. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts.

6Mayer, K. J., & Barnes, E. A. (2021). Subseasonal forecasts of opportunity identified by an explainable neural network. Geophysical Research Letters, 48.

7Mamalakis, A., Ebert-Uphoff, I., Barnes, E. (2022). Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Meteorology and Climate Science: Model Fine-Tuning, Calibrating Trust and Learning New Science. Invited book chapter.

8Mamalakis, A., Ebert-Uphoff, I., & Barnes, E. (2022). Neural network attribution methods for problems in geoscience: A novel synthetic benchmark dataset. Environmental Data Science, 1, E8.

9Mayer, K. J., & Barnes, E. A. (2022). Quantifying the effect of climate change on midlatitude subseasonal prediction skill provided by the tropics. Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL098663.