Heatwaves, Cow Farts, and the Perfect Beach Spot: Sorting Through the Science of Climate Change

ICYMI the climate is changing. Between the ~ unprecedented ~ fires, floods, and heatwaves along with the recent release of the 6th Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6), it is more clear than ever: our climate is changing, these changes are happening globally, and humans are unequivocally the cause. 1

But how exactly are we to blame? How do our actions physically alter the global climate? Are all extreme weather events now caused by climate change? Seasoned Chaos is here to help answer some of these questions, clarify misconceptions surrounding climate change, and shed light on the nuance of this thing called attribution.

Greenhouse gases – the link between humans and climate change

For our planet to be habitable, we need greenhouse gases (GHGs)! They act sort of like Earth’s blanket, helping to regulate the temperature of the earth through the greenhouse effect. However, at our current state and concentration of GHGs, it’s more like a winter comforter, trapping more heat. Oh, and we can’t take the comforter off.

The greenhouse effect from NASA Climate

Humans emit GHGs, such as carbon dioxide, at alarming, non-natural rates, so much so that carbon dioxide concentrations detected are the highest they have ever been in 2 million years.1 Other GHGs, such as methane and nitrous oxide, are also their highest in 800,000 years.1 There is no longer any doubt that human activity is responsible for this spike in GHG concentrations and driving the warming of our planet.1,2,3 Plus, while cow farts are often to blame for contributing a sizable amount of methane, they don’t fart this much.4

It’s getting hot in here – so please upcycle all your clothes

As a direct result of GHG increase, the average global surface temperature has risen 2.1°F (1.18°C) since the late 19th century.2,5 This temperature rise triggers a domino-like effect of consequences occurring all over the globe: glacial retreat, warming of the oceans and their acidification, sea level rise, changes in agricultural regions and growing seasons, more droughts and heat waves, as well as changes in precipitation patterns—to name a few.1

All these changes reported by the IPCC are a summary of scientific literature presented with quantifiable, varying degrees of confidence at which they have been detected and attributed. Detection and attribution are the ways in which climate scientists link the ‘what’ to the ‘why’.

You know my methods, Watson

Detection is the ‘what’ and is a quantitative measure of a change in the climate system, without providing a reason for that change.6,7 It is important to note that detected changes are those separate from the expected ups and downs or natural variability of a system.6,7

Attribution is the ‘why’ and is a complex process that determines the multiple factors of a detected change or event. Pairing statistical means with physical understanding, attribution helps us determine how much of an event is caused by human influence and how much is natural.6,7

Scientists use phrases such as unlikely, very likely, or medium, high confidence to summarize detection and attribution. While many of the aforementioned consequences from the IPCC AR6 are reported on the higher end of likelihood and confidence, not all changes to our global climate are as clear-cut.

Climate does not cause weather, it affects it

Climate and weather are not the same phenomenon–as we have explained, climate is long term averages of weather variables.8 Weather is short term, local conditions that depend on many factors. Recall our weather pattern pie and how weather can be influenced by local circulations, ENSO, seasons, and more, all acting at various spatial scales and time scales.

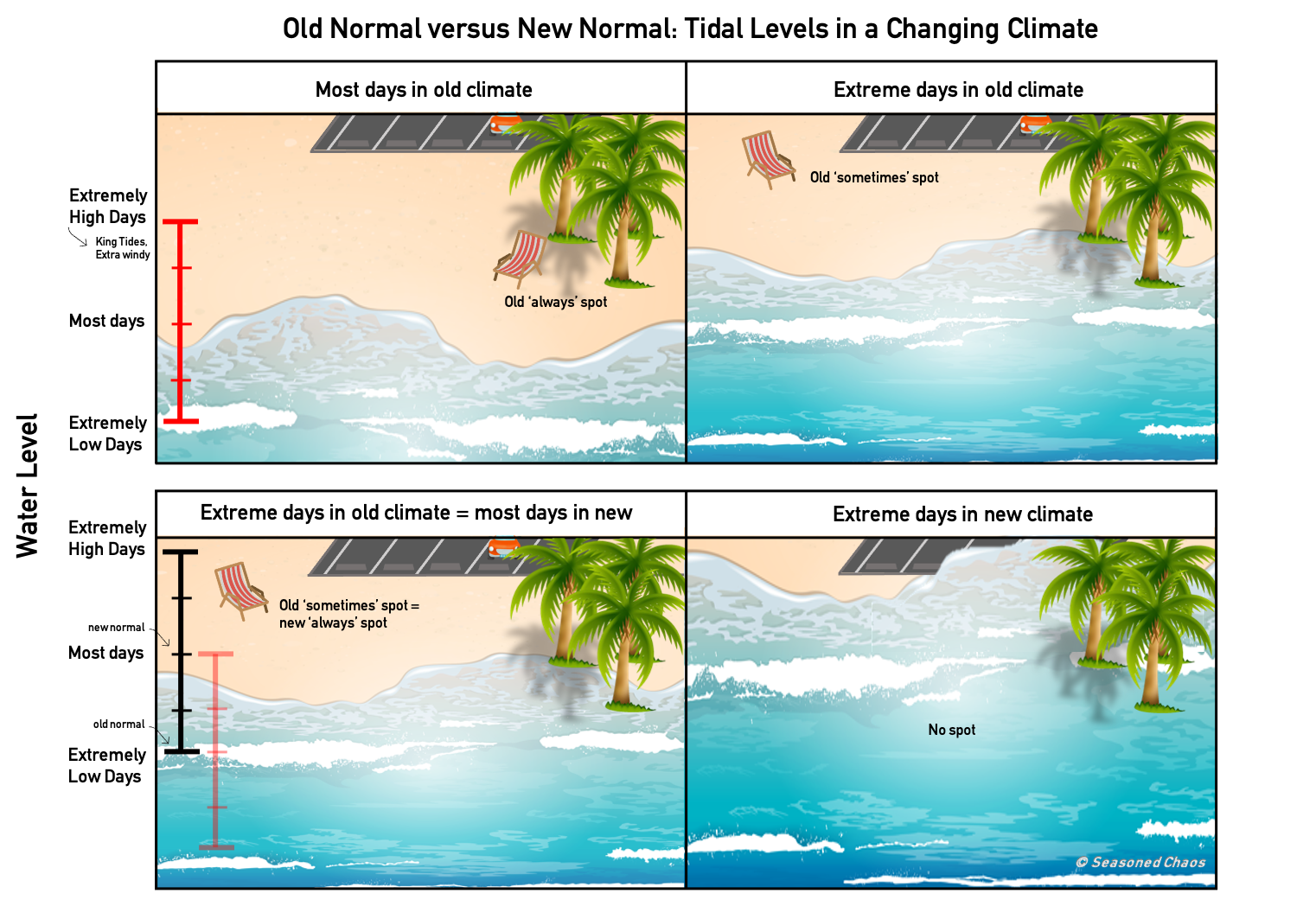

Let’s consider this from the beach, with your toes in the sand, waiting for the expected high tide to slowly reach your feet. You have been to this beach since you were a child and with some help from your weather app, the season, and the moon, you know justtt when that might happen.

Except, gradually, the water is getting closer and closer to that perfect shady spot where you place your chair. High tide starts around the time you expect, but your perfect spot has been inundated. You have to use your backup spot, the one you only sometimes use on windier days when the waves are higher, or during those pesky King Tides.

Figure 1: A depciction of how climate change is influencing background conditions and increasing the chances of extremes.

What you expected to occur – the high tide happening at a certain time – still does, but the background conditions are different and your backup spot is now your “always” spot. And the King Tides are more extreme than ever. There is no spot for your chair; the parking lot is usually flooded then, too. The push and pull of the tides are still happening. It is their nature – they are just pushing and pulling farther inland than before. Climate variables are often considered background or antecedent conditions that influence the type of weather we may expect. The old extreme is the new normal. New normals or a shift in the average conditions also results in ‘new’ or higher chances of extremes to occur.

Climate change is therefore 1) influencing the background conditions at which weather happens and 2) changing the likelihood that extreme weather events may occur. Both effects are also not always occurring simultaneously. This is an added challenge of attribution and understanding to what degree human caused climate change is contributing to our weather events.

Normal weather in a ~new-normal~ climate

The heat wave over the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. of this past 2021 summer is an example of understanding the nuance of attribution. From June 27-29th temperatures reached triple digits, causing extreme conditions for communities in that region. Following a rapid attribution study presented by the World Weather Attribution, the temperatures experienced would have been “virtually impossible” without human-induced warming.9

But the actual weather phenomena behind the event, atmospheric blocking, was not a wildly abnormal occurrence for the region; WWA found this account as “likely not exceptional.”9 Blocking is known to cause extreme weather conditions. In fact, 80% of Northern Hemisphere six-hourly warm temperature extremes can be linked to blocking events.10 Other regional factors such as localized drought and topography may have also played a role.9 In short, there was a ‘normal’ weather event acting in a changed climate.

Attribution is tricky, and every event is different, but getting it right is important in order to maintain scientific integrity and help us, as a global community, become as resilient as possible in the wake of a warming world.

Footnotes:

1 IPCC AR6 Summary for Policy Makers

2 NASA Climate

3 Climate.gov article

4 EPA breakdown of greenhouse gas emission sources in the U.S.

5 Luthi, D., et al.. 2008; Etheridge, D.M., et al. 2010; Vostok ice core data/J.R. Petit et al.; NOAA Mauna Loa CO2 record.

6 IPCC 2018 Special Report Chapter 10 on detection and attribution

7 Detection and attribution from the National Climate Assessment

8 IPCC glossary

9 World Weather Attribution rapid study on the Pacific Northwest heatwave of June, 2021

10 Pfahl, S., and Wernli, H. (2012), Quantifying the relevance of atmospheric blocking for co-located temperature extremes in the Northern Hemisphere on (sub-)daily time scales, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L12807, doi:10.1029/2012GL052261.