Part I: A Sprinkle of Monsoon Magic

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear “monsoon”? Typically, we associate monsoons with rain… and lots of it. But the word monsoon actually comes from the word mausim, an Arabic word meaning season of winds. The actual definition of monsoons is a shift in winds, which is tied to the seasons. Winds ultimately affect the amount of rainfall different regions receive. But how does this actually work?

Bear with us for a moment as we dive into some thermodynamic basics. Let’s imagine the following scenario: In May/June, the temperatures are starting to warm up and you are ready to head to the ocean/quarry/lake (depending on where you live) and you jump in the water but BRR! The water is freezing! But come September/October, the temperatures outside are cooling down, but the water is still nice and warm- maybe even warmer than the temperature outside! This difference is caused by water having a higher specific heat than air, meaning it takes more energy to warm water by 1 degree than it does to warm air by 1 degree. Since the water takes much longer to change temperature than the air, this creates noticeable differences in the air and water temperature depending on the season. Monsoons depend on this very same principle.

Monsoons 101

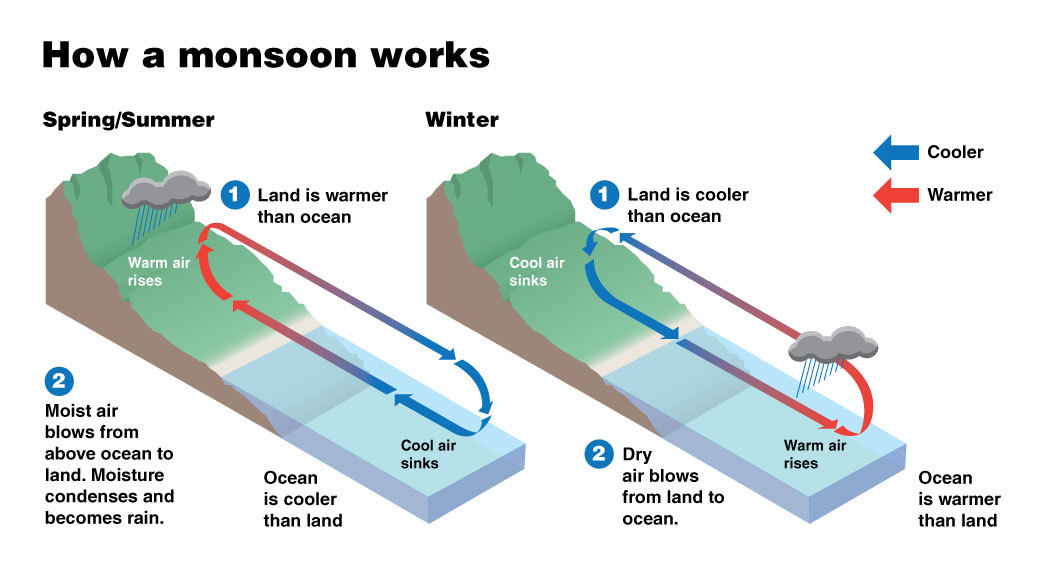

Monsoon winds always blow from cold to warm temperatures, i.e. from high to low pressure. During the late spring and early summer, the land starts to heat up faster than the surrounding water. This causes the air at the surface to expand and rise, creating low pressure at the surface**. As the warm air rises, it condenses into clouds, creating convection, or storminess (see below animation). The air flows outward at the top of the atmosphere, flowing towards the ocean. This air then sinks, creating a high pressure with cold air at the ocean surface. Since the air flows from high to low pressure, the cold, moist air moves over the land, closing the atmospheric loop, and driving the “rainy season” of the monsoon cycle.

Adapted from our MJO post, the circulation for converging air at surface, causing storminess, and diverging air at upper levels, causing sinking air in surrounding regions.

As the seasons change, so do the monsoons. In the late fall and winter, the air temperature drops quickly, while the ocean water remains warm, causing the monsoon loop to reverse. The warm ocean causes low pressure at the surface, and the air just above the warm ocean warms and begins to rise. This creates rainfall over the ocean. The air travels along the top of the atmosphere from the ocean to the land. Since the air is now cooler over the land, the air begins to cool and sink toward the surface, resulting in dry conditions over land, i.e. the “dry season”. There is now high pressure and cold air at the land surface, so the air flows toward the low pressure in the ocean, creating the reverse loop of the monsoon.

A diagram showing how seasonally evolving temperature differences between land and ocean drive monsoon circulations. From NASA SciJinks, credit to NOAA/JPL.

A Global Phenomenon

The most famous of the monsoons is the Asian monsoon near India and South Asia, but monsoons occur in North America, South America, Australia, and in many tropical climates with a land-sea contrast. More than half of the world’s population lives in a climate influenced by monsoons.

Given that the Asian monsoon is such an important part of society for much of the world’s population, it would be great if we could predict it in advance. Fortunately, there are some useful climate relationships that help with seasonal forecasting of the monsoon, mostly due to the circulations of rising and sinking air that we described above.

A Bite out of our Weather Pattern Pie: ENSO + IOD

First, as mentioned in the spring predictability barrier post, the monsoon and ENSO have a bit of a tug of war. When ENSO is in its warm phase, the Asian monsoon is typically in its weak phase, and when ENSO is in its cool phase, the Asian monsoon is typically in its strong phase. ENSO affects the locations of branches of rising air (convection and storminess) and sinking air (dryness and sunny skies) over the tropical Pacific. Let’s think about El Nino as an example: El Nino will cause rising air over the central-eastern Pacific, and sinking air over India, southeast Asia, and Indonesia regions. Sinking air = dryness, so the monsoon is expected to weaken.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) has also been known to have a relationship with the monsoons. The Indian Ocean also has fluctuating sea surface temperatures (SSTs) that can impact the strength of the monsoon (for the nerds out there, you can read more about the Indian Ocean Dipole here). Similar to ENSO, regions of warm vs. cool SSTs can affect locations of branches of rising and sinking air. For instance, if SSTs are warm over the west tropical Indian Ocean and cool over the east tropical Indian Ocean, this generally enhances the monsoonal rainfall over India due to rising air and decreases monsoonal rainfall over southeast Asia due to sinking air.

The anomalous SSTs and circulation associated with (looping through): El Niño (warm ENSO), positive IOD, then El Niño + IOD. Notice they have have a sinking branch in the eastern Indian Ocean.

But wait- there's more?!

In short, large-scale climate can influence monsoon strength and cycles, which can drastically affect the rainfall received by most of the global population. However, because the summer monsoon itself is such a dominant global feature, it can exert its own influence on global climate patterns. Come back monSOON for our part II post to find out more!

**Let’s take an imaginary box of air which allows air to pass in and out. If the air inside of the box heats, the air will expand, causing some molecules to escape the box. There are now less molecules inside the box, creating low pressure.