The View From Our Window: Celebrating 5 years of Seasoned Chaos and S2S Research

Can you believe it’s been five years since Seasoned Chaos started?! This journey began with our debut post in December 2019 on the challenges and necessities of forecasting on S2S (subseasonal-to-seasonal) timescales, or roughly 2 weeks to 3 months in advance. Seasoned Chaos has covered dozens of topics, highlighting the global climate patterns associated with higher S2S forecast skill. Sprinkles of chaos in the climate system make S2S forecasting quite the challenge. Given that this is such a challenging time frame on which to make predictions, we can’t always make good forecasts. But we can pinpoint particular states of the climate system which lead to more predictable conditions a few weeks to a few months later. We call these S2S windows of opportunity.

An excellent review on S2S windows of opportunity is provided by Mariotti et al. 20201. Windows of opportunity refer to states of the climate system which provide higher S2S forecast skill and confidence in those predictions (which can vary regionally, seasonally, etc.). This overview paper pointed out a number of underutilized sources of S2S predictability. While this area of research is still actively being investigated, including by your very own Seasoned Chaos team, a number of advancements in S2S prediction have been made since our very first post. Peering through our Seasoned Chaos portfolio, let’s explore recent progress of finding these windows.

We make a note here that this should not be seen as a comprehensive review of all progress made in S2S prediction since the start of the decade. Rather we highlight new research on topics covered by Seasoned Chaos and how these have contributed to advances in S2S prediction and general understanding of our climate system. In this post, windows of opportunity sections are organized as such: first, we give an overview of the dominant teleconnections that describe global climate, then, we outline by “impact” with discussions on remote influences (i.e., relevant sources of the predictability from the aforementioned teleconnections).

General Climate (temperature and precipitation patterns and their extremes)

MJO and ENSO teleconnections

Starting out with some of our favorites, tropical sources of heating – primarily MJO and ENSO – dominate S2S predictability. Need a refresher? The MJO is defined by large-scale, slow-moving storminess moving across the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans. ENSO is defined by monthly fluctuations in the tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs).

When Western Pacific SSTs are warm, MJO activity is stronger, leading to windows of increased subseasonal forecast skill2. Errors of opportunity (the opposite of a window of opportunity, when we know we can’t predict the future well) have been identified for S2S predictions in the Northern Hemisphere based on the MJO and its summer cousin, the Boreal Summer Intraseasonal Oscillation (BSISO)3.

Certain coinciding MJO and ENSO phases can lead to enhanced S2S forecast skill for U.S.4 and South America5 precipitation. While the MJO does lead to windows of opportunity, ENSO remains King! ENSO can impact the jet stream, leading to higher predictability of monthly circulation patterns6. Overall, ENSO has been shown to be more useful in S2S Northern Hemisphere circulation predictions than other climate patterns7.

Monsoon teleconnections

Grab your pool floaty! Recently explored sources of (sub)tropical heating via monsoon-related BSISO and circumglobal teleconnection (CGT) can also explain S2S predictability. In general, monsoon teleconnections are emerging as important drivers of Northern Hemisphere summer weather and climate extremes.

For instance, the Indian monsoon and East Asian monsoon influence mid-latitude circulation on the seasonal timescale8,9. The BSISO is linked to U.S. summer precipitation events10 and U.S. west coast heat waves11,12.

Stratosphere teleconnections

Most weather happens in the troposphere, but predictability of tropospheric weather can come from the atmospheric layer directly above it – the stratosphere. The stratosphere primarily influences weather and climate over the North Atlantic region, often defined by the phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).

Significant polar vortex anomalies in the lower stratosphere during May can exert significant downward influence on summer NAO13. In addition, late winter sudden stratospheric warmings (SSWs) may provide windows of opportunity. Weak polar vortex leads to more predictable regimes14. SSWs are more predictable when they are preceded by a tightening of the polar vortex away from the subtropics, and when stratospheric winds are more easterly15.

PNA and NAO teleconnections

Our telenovela stars, the Pacific-North America (PNA) pattern and NAO, remain important for describing mid-latitude circulation variability and subseasonal predictability of Northern Hemisphere climate16. Monthly (and seasonal) predictions of the NAO are only weakly related to medium-range skill.

In addition to the traditional view of using PNA and NAO, weather regimes are another way to understand S2S predictability. Weather regimes by construction represent naturally persistent atmospheric states; therefore, long-lived regimes may offer S2S forecast opportunities17.

Tropical Cyclones

Tropical cyclone forecasting has been particularly difficult in the subseasonal range as our typical dynamical model approaches to forecasting don’t really work for subseasonal forecasts. However, statistical dynamical approaches to TC prediction look promising. This statistical-dynamical method uses dynamical forecasts of broader fields or “ingredients”, like a GFS (U.S. forecasting model) forecast of vertical wind shear or convection, then statistically relates them to TC activity. With these methods, skill can be found weeks in advance.

Recent studies have also shown that some predictability is coming from the mid-latitudes, a deviation from our typical tropical MJO-centric paradigm. Seasonal TC prediction in the Atlantic is tied to Rossby wave breaking events18, which is when the jet stream amplifies to the point where it folds in on itself. This can cause high shear and dry air intrusions in the Atlantic that inhibit TC activity. The MJO can influence Atlantic TC activity through extratropical pathways including Rossby wave breaking19,20. This differs from previous literature that emphasized the MJO circulation itself was what primarily influenced shear and humidity that resulted in changes in TC activity.

Severe Weather

Hurricane season is over, so it’s time to head down the yellow brick road. Severe weather impacts, e.g., tornadoes and hail, are considered “unpredictable” past a couple hours, but broad U.S. tornado/hail activity – represented by storm “ingredients” – might be predictable on the subseasonal timescale21,22.

One of the strongest S2S signals is from ENSO (#king): La Niña is linked to enhanced severe weather activity23,24, though La Niña is also linked to lower predictability (forecast skill) of severe weather events25. An active MJO makes it easier to accurately predict tornadoes and hail26, and persistent PNA events often precede impactful severe weather events27.

Atmospheric Rivers

After visiting Oz, let’s take a whitewater rafting trip down an atmospheric river. Windows of opportunity for S2S prediction of atmospheric rivers along the western U.S. have been identified based on the state of ENSO, the PNA pattern, and the Arctic Oscillation28.

Different flavors of ENSO and MJO phases can result in higher atmospheric river predictability29. Ever important is the MJO, which is linked to western U.S. atmospheric river S2S predictability30.

Stratospheric variability (like the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation, or QBO – not sure what this is? Coming to a SC post near you! ![]() ) has also been shown recently to create windows of opportunity for S2S atmospheric river prediction, particularly during certain coinciding phases of both the MJO and QBO31,32.

) has also been shown recently to create windows of opportunity for S2S atmospheric river prediction, particularly during certain coinciding phases of both the MJO and QBO31,32.

Sea Levels / Coastal Flooding

Next let’s invest some time on the coasts. Certain coinciding MJO and ENSO phases can lead to enhanced S2S forecast skill for U.S. coastal sea levels33. However, in the current generation of climate models, there is low seasonal forecasting skill for monthly sea level anomalies on the East Coast of the U.S. (an area of hot spots of sea level rise in recent years). This is in contrast to skillful S2S forecasts for the West Coast/Pacific34; sea surface heights along the U.S. West Coast are more predictable when extreme coastally trapped wave conditions are present35.

Emerging Tool: AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a global buzzword since Seasoned Chaos first began, so it comes as no surprise that AI is being used to better our understanding and forecasting of S2S impacts. AI has been used for pinpointing teleconnections and improving extreme weather prediction.

Worried about the “black box” or potential unknowns of AI? Explainable and interpretable AI can help to identify sources of S2S predictability36-39. We are currently in the dawn of purely AI-driven models for weather-to-climate forecasting, making this an exciting time for S2S forecasting developments. Some of the hottest models making weather predictions at the fraction of the speed of our traditional weather forecasting models (as of the time this article came out) are GraphCast40, foundation models such as Aurora41, and hybrid dynamical-AI models such as NeuralGCM42.

5 Years Later...

All in all, a lot of research and progress has happened over the last several years, leading to better understanding of windows of opportunity in S2S prediction. Still, there are a lot of unknowns (great, we get to keep our jobs and continue this blog!)… Are there other sources for windows of opportunity that we haven’t found yet? Is there a limit to what we can predict on S2S timescales? Plus, we did not include topics we haven’t discussed in SC that warrant their own dedicated post and investigation (e.g. the role of soil moisture in S2S prediction).

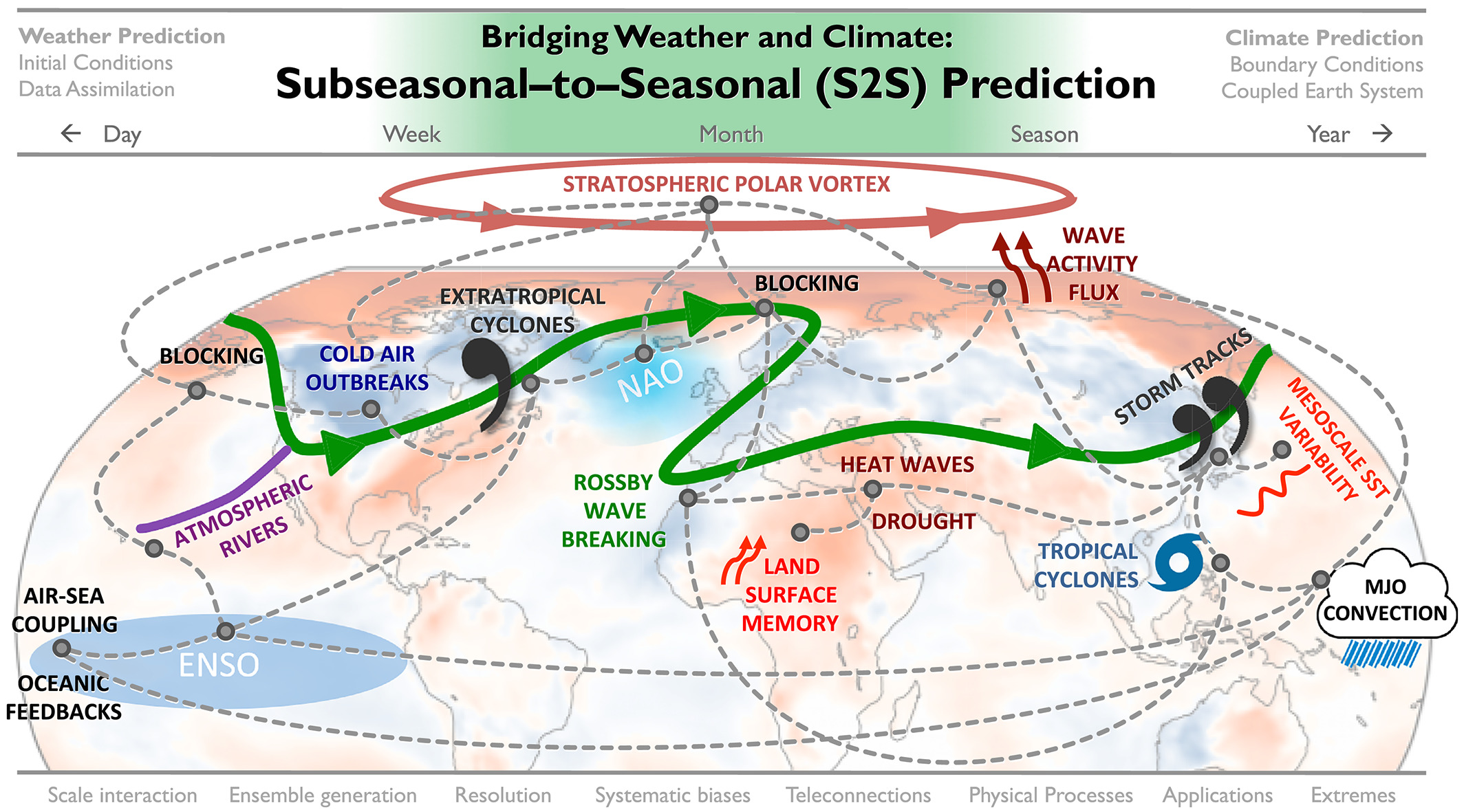

An overview of all relevant processes involved in S2S predictability. Taken from [43].

Comment below what your favorite SC post(s) have been so far. From all of us at Seasoned Chaos, thanks for reading over these last few years! ![]()

Footnotes:

- Mariotti, Annarita, et al. “Windows of opportunity for skillful forecasts subseasonal to seasonal and beyond.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 101.5 (2020): E608-E625.

- Liu, Xiaolei, et al. “To identify the forecast skill windows of MJO based on the S2S database.” Geophysical Research Letters 51.16 (2024): e2024GL109903.

- Cahill, Jack, et al. “Errors of Opportunity: Using Neural Networks to Predict Errors in the Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS) on S2S Timescales.” Weather and Forecasting (2024).

- Arcodia, Marybeth C., Ben P. Kirtman, and Leo SP Siqueira. “How MJO teleconnections and ENSO interference impacts US precipitation.” Journal of Climate 33.11 (2020): 4621-4640.

- Fernandes, L. G., and A. M. Grimm, 2023: ENSO Modulation of Global MJO and Its Impacts on South America. Journal of Climate, 36, 7715–7738.

- Chapman, William E., et al. “Monthly modulations of ENSO teleconnections: Implications for potential predictability in North America.” Journal of Climate 34.14 (2021): 5899-5921.

- Mayer, Kirsten J., William E. Chapman, and William A. Manriquez. “Exploring the relative importance of the MJO and ENSO to North Pacific subseasonal predictability.” Geophysical Research Letters 51.10 (2024): e2024GL108479.

- Di Capua, G., et al. “Dominant patterns of interaction between the tropics and mid-latitudes in boreal summer: Causal relationships and the role of time-scales.” Weather and Climate Dynamics Discussions, 2020, 1-28.

- Malloy, K., & Kirtman, B. P. “The summer Asia–North America teleconnection and its modulation by ENSO in Community Atmosphere Model, version 5 (CAM5).” Climate Dynamics 59.7 (2022): 2213-2230.

- Malloy, K., & Kirtman, B. P. “Subseasonal Great Plains Rainfall via Remote Extratropical Teleconnections: Regional Application of Theory‐Guided Causal Networks.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 128.5 (2023): e2022JD037795.

- Lin, H., Mo, R., & Vitart, F. “The 2021 western North American heatwave and its subseasonal predictions.” Geophysical Research Letters 49.6 (2022): e2021GL097036.

- Lubis, S. W., et al. “Enhanced Pacific Northwest heat extremes and wildfire risks induced by the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation.” npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 7.1 (2024): 232.

- Dunstone, N., et al. “Skilful predictions of the summer North Atlantic Oscillation.” Communications Earth & Environment 4.1 (2023): 409.

- Spaeth, J., et al. “Stratospheric impact on subseasonal forecast uncertainty in the northern extratropics.” Communications Earth & Environment 5 (2024): 126.

- Chwat, D., et al. “Which sudden stratospheric warming events are most predictable?” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 127 (2022): e2022JD037521.

- Yamagami, A., & Matsueda, M. “Subseasonal forecast skill for weekly mean atmospheric variability over the Northern Hemisphere in winter and its relationship to midlatitude teleconnections.” Geophysical Research Letters 47.17 (2020): e2020GL088508.

- Lee, S. H., Tippett, M. K., & Polvani, L. M. “A new year-round weather regime classification for North America.” Journal of Climate 36.20 (2023): 7091-7108.

- Jones, J. J., M. M. Bell, and P. J. Klotzbach. “Tropical and Subtropical North Atlantic Vertical Wind Shear and Seasonal Tropical Cyclone Activity.” Journal of Climate 33 (2020): 5413–5426.

- Hansen, K. A., et al. “Impact of MJO propagation speed on active Atlantic Tropical Cyclone activity periods.” Geophysical Research Letters 51 (2024): e2023GL106872.

- Chang, C.-C., et al. “An extratropical pathway for the Madden–Julian Oscillation’s influence on North Atlantic tropical cyclones.” Journal of Climate 36.24 (2023): 8539–8559.

- Wang, H., Kumar, A., Diawara, A., DeWitt, D., & Gottschalck, J. “Dynamical–statistical prediction of week-2 severe weather for the United States.” Weather and Forecasting 36.1 (2021): 109-125.

- Lee, S. K., Lopez, H., Kim, D., Wittenberg, A. T., & Kumar, A. “A seasonal probabilistic outlook for tornadoes (SPOTter) in the contiguous United States based on the leading patterns of large-scale atmospheric anomalies.” Monthly Weather Review 149.4 (2021): 901-919.

- Malloy, K., & Tippett, M. K. “A Stochastic Statistical Model for US Outbreak-Level Tornado Occurrence Based on the Large-Scale Environment.” Monthly Weather Review 152.5 (2024): 1141-1161.

- Tippett, M. K., Malloy, K., & Lee, S. H. “Modulation of US tornado activity by year-round North American weather regimes.” Monthly Weather Review 152.9 (2024): 2189-2202.

- Miller, D. E., & Gensini, V. A. “GEFSv12 High-and Low-Skill Day-10 Tornado Forecasts.” Weather and Forecasting 38.7 (2023): 1195-1207.

- Miller, D. E., Gensini, V. A., & Barrett, B. S. “Madden-Julian oscillation influences United States springtime tornado and hail frequency.” npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 5.1 (2022): 37.

- Kim, D., Lee, S. K., Lopez, H., Jeong, J. H., & Hong, J. S. “An unusually prolonged Pacific-North American pattern promoted the 2021 winter Quad-State Tornado Outbreaks.” npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 7.1 (2024): 133.

- Zhang, W., et al. “Subseasonal-to-seasonal (S2S) prediction of atmospheric rivers in the Northern Winter.” npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 7.1 (2024): 275.

- Huang, Huanping, et al. “Sources of subseasonal‐to‐seasonal predictability of atmospheric rivers and precipitation in the western United States.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126.6 (2021): e2020JD034053.

- Zhang, Zhenhai, et al. “Multi‐Model Subseasonal Prediction Skill Assessment of Water Vapor Transport Associated With Atmospheric Rivers Over the Western US.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 128.7 (2023): e2022JD037608.

- Mayer, Kirsten J., and Elizabeth A. Barnes. “Subseasonal midlatitude prediction skill following quasi-biennial oscillation and Madden–Julian Oscillation activity.” Weather and Climate Dynamics 1.1 (2020): 247-259.

- Castellano, Christopher M., et al. “Development of a statistical subseasonal forecast tool to predict California atmospheric rivers and precipitation based on MJO and QBO activity.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 128.6 (2023): e2022JD037360.

- Arcodia, Marybeth C., Emily Becker, and Ben P. Kirtman. “Subseasonal Variability of US Coastal Sea Level from MJO and ENSO Teleconnection Interference.” Weather and Forecasting 39.2 (2024): 441-458.

- Long, X., et al. “Seasonal forecasting skill of sea‐level anomalies in a multi‐model prediction framework.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 126.6 (2021): e2020JC017060.

- Amaya, D. J., et al. “Subseasonal‐to‐seasonal forecast skill in the California Current System and its connection to coastal Kelvin waves.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 127.1 (2022): e2021JC017892.

- Mayer, K. J., & Barnes, E. A. “Subseasonal forecasts of opportunity identified by an explainable neural network.” Geophysical Research Letters 48.10 (2021): e2020GL092092.

- Molina, Maria J., et al. “A review of recent and emerging machine learning applications for climate variability and weather phenomena.” Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems 2.4 (2023): 220086.

- Arcodia, Marybeth C., et al. “Assessing decadal variability of subseasonal forecasts of opportunity using explainable AI.” Environmental Research: Climate 2.4 (2023): 045002.

- Arcodia, M., et al. “Sea Surface Salinity Provides Subseasonal Predictability for Forecasts of Opportunity of U.S. Summertime.” Environmental Research: Climate (2024).

- Lam, Remi, et al. “Learning Skillful Medium-Range Global Weather Forecasting.” Science 382.6677 (2023): 1416–1421.

- Bodnar, Cristian, et al. “Aurora: A foundation model of the atmosphere.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13063 (2024).

- Kochkov, Dmitrii, et al. “Neural general circulation models for weather and climate.” Nature 632.8027 (2024): 1060-1066.

- Lang, A. L., Pegion, K., & Barnes, E. A. (2020). Introduction to special collection: “Bridging weather and climate: Subseasonal-to-seasonal (S2S) prediction”. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 125, e2019JD031833.